Get growing! It’s just about time to start those tomato, pepper, and eggplant seeds. Here are some tips to show you how:

L: Numex Twilight peppers; C: Orange Blossom tomatoes; R: Orient Express eggplants.

Photos: Johnny’s Selected Seeds.

The Solanacea (Nightshade) family bears arguably the most prized of our “vegetable” crops. We all know the difference between a fruit and a vegetable, right? Fruits are parts of a plant that contain the seeds while a vegetable is any other part of the plant that we consume – the leaves (kale, onions), the stem (rhubarb, celery), the root (parsnip, burdock), etc. So what about our dear eggplants, peppers, tomatoes? That’s right – they’re fruits. We especially don’t eat the vegetative parts of these plants because they are toxic. A potato (although we use the tuber for propagation) is a vegetative part as potatoes produce lovely flowers (and seeds!)

Potato flowers. Photo: offshoots.org.uk.

Tomatoes, peppers and eggplants are warm season crops. Because of our relatively short growing season in Vermont, plants must either be bought or started soon. Most nurseries carry standard varieties like Beefsteak, Lady Bell, etc. but the best part about starting your own is that you can spice things up with Numex Twilight or go lovely with Bianca. You can also decide if you want to grow determinate tomatoes (bush varieties that do not need pruning/staking and fruit ripens in a concentrated time) like my favorite Orange Blossom, heirloom varieties paramount for taste like Cherokee Purple, or indeterminate (if you want to toss a few in the salad over the whole summer and are willing to do some staking/pruning) like my other favorite Sungold or New Girl. For something different in eggplant land try Calliope or Orient Express, which is reliable to set fruit in cooler weather, and has a lovely flavor especially when wrapped in aluminum with a little olive oil, salted and grilled….

L: Cherokee Purple tomatoes;R: Calliope eggplants. Photos: Johnny’s Selected Seeds.

Start by knowing the average last frost date for your region. Using the days to maturity listed on your seed packet, count backwards from this date to find the best week to start your seeds (for warm season crops, go by the dates listed under 10% probability). It is better to have strong, growing plants, than those that are stunted either because they are set out too early or have been hanging out inside too long and have become leggy. Peppers are about 60 days to green fruit and another 20 to red or yellow fruit. Eggplants are around 60 days while tomatoes can range from 50-80 days, depending on variety.

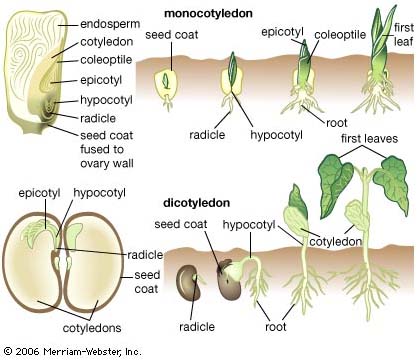

Stages of seed and seedling development. Image: Merriam-Webster, Inc.

For tomatoes, sow seeds in a flat (or for a homemade flat, cut a juice carton in half lengthwise and poke holes in the bottom) using a soil-less peat-based mix kept at 75-90°F for best germination (you may want to use a heat mat to maintain these temperatures). Start plants 5-6 weeks before they will be transplanted outside. When the first true leaves (not the cotyledon) develop, transplant into bigger pots and continue to grow at 60-70°F. You can make your own paper pots, go biodegradable, or use plastic ones, but make sure that they are at least 3 inches deep. Water only to keep the soil-less mix from drying out, and fertilize with a soluble fertilizer like fish emulsion or compost tea. When transplanting out to the garden, you can use black or red plastic “mulch” to trap light and encourage photosynthesis (not hay mulch around tomatoes because of disease). When you move your transplants outdoors, make sure you know how to prune/stake, and cover plants with row cover if temperatures are low.

A paper pot maker. Photo: Gardener’s Supply Co.

For peppers, sow in shallow flats, ¼” deep in well-drained, fertile soil abundant in phosphorus (bone meal should be available at your local garden center) and calcium, 8 weeks prior to transplanting outdoors. Peppers also like it hot so try to keep soil temperature at 80-90°F. Transplant into larger containers when first true leaves show and grow at 70°F during the day and 60°F at night until they’re ready to go in the garden.

For eggplants, sow in flats 8 weeks prior to planting outside, ¼” deep in soil that is 80-90°F until plants emerge (important) and then at 70°F. When the first true leaves appear, thin the flat so that each plant is 2-3” apart or transplant into individual cells. Eggplants are especially sensitive to cold so make sure to harden off and use row cover to increase performance at the beginning of the season.

It’s important to remember that the conditions described above are ideal–seeds and plants are naturally resilient and will grow in conditions short of perfect, but it’s always best to follow recommendations as closely as possible. And if things don’t go exactly as planned, there’s always the nursery!

Very clear article — thank you. I do wonder, though, if anyone is making that black or red plastic mulch in a biodegradable form? I’m not wild about everyone using up yards and miles of non-biodegradable plastic material.

Hi Steve,

Here are some more eco-friendly mulching options:

Biodegradable corn starch based mulch from High Mowing Seeds and Johnny’s Selected Seeds, or paper mulch from Johnny’s. (roll over for links)

-Anna

Great info! Right off the bat you start to answer one of my perennial questions – what is the difference between a fruit and a vegetable? I always think of it as – a fruit is a botanical term & a vegetable is a nutritional term…. Does this make sense? Any more information about this?

Thanks, Anna, I am excited to start my tomatoes and peppers this weekend!

Nix vs. Hedden

In 1893, a case was filed by John Nix, John W. Nix, George W. Nix, and Frank W. Nix against Edward L. Hedden, a tax collector of the Port of New York. They wanted to recover duties paid under protest, because of the Tardif Act of March 3, 1883, which required tax to be paid on imported vegetables, but not on fruits. The case went to the US Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the defendant unanimously. The court determined that for tax purposes, the tomato should be classified based on the way that it was used, not based on its botanical meaning.

Read more at Suite101: Is a Tomato a Fruit or a Vegetable?: Choosing the Right Classification for Tomatoes http://botany.suite101.com/article.cfm/is_a_tomato_a_fruit_or_a_vegetable#ixzz0iip7iLS1

This question is an interesting one! Wikipedia gives a thorough explanation from both the botanical and cultural sides.