By Julie Moir Messervy

On May 3, The New York Times published an op-ed piece by creative writing professor James Barilla that advocates maximizing diversity in our gardens in the face of a changing and unpredicatble climate. Barilla writes, “It doesn’t make sense to think in terms of native and nonnative when the local weather vacillates so abruptly. A resilient garden is a diverse garden.” He goes on to quote “a study done in Davis, CA,” that he says shows that 29 of 32 native butterflies feed on nonnative plants. Although I couldn’t find this study online to read more about it, I did find the website of Dr. Arthur Shapiro at UC Davis.

Dr. Shapiro has been studying butterflies for 34 years and has a host of fascinating observations to share. His 2010 study covering 159 species of butterfly that were monitored for over 35 years includes these findings:

- Butterfly diversity (the number of different species present) is falling fast at all the sites near sea level, in the central valley, and the foothills. It is also declining, but more slowly, in the mountains.

- The highest monitoring sites, at tree line, show an increase in butterfly diversity, as lower-elevation species react to the warming climate by moving upslope to higher, cooler elevations.

- However, among butterflies adapted to the highest elevations, the number of species is beginning to fall because temperatures are becoming uncomfortably warm for them, and, Shapiro says, “There is nowhere to go except heaven.” (Courtesy of Science Daily)

I’m a landscape designer, not a scientist. For information, I turn to those in the know like Professor Doug Tallamy of the University of Delaware. Doug has long espoused the importance of planting native plants instead of our barren lawns and exotic species around our houses and neighborhoods.

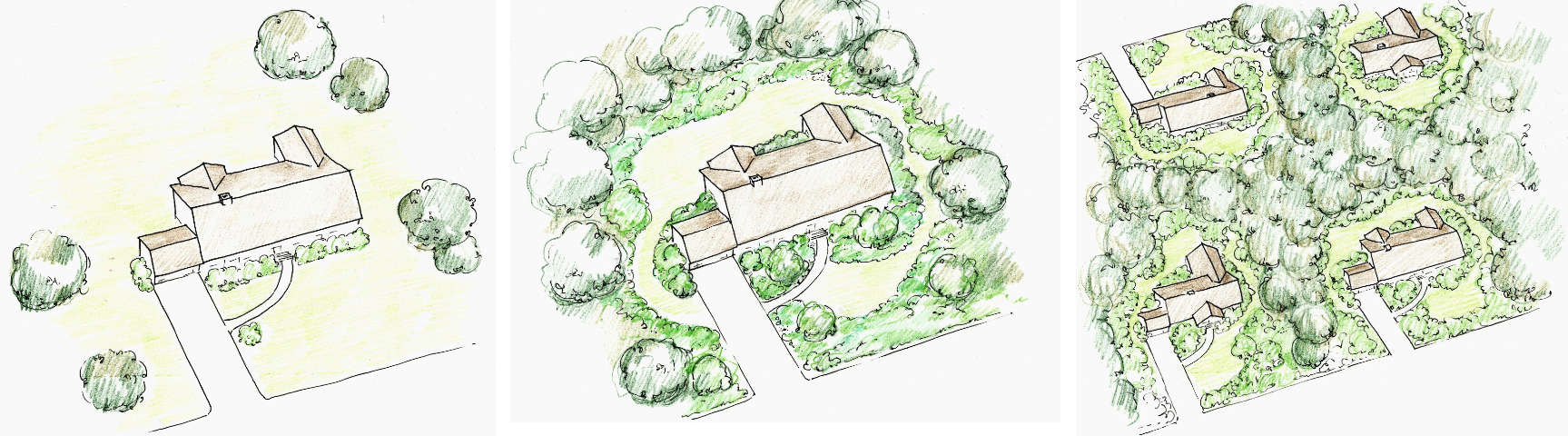

“Restoring native plants to most human-dominated landscapes is relatively easy to do,” Doug says. He suggests planting belts of native trees, shrubs, and perennials around the perimeter of your yard, while placing your favorite exotic species, like Japanese maples, azaleas, and tulips, nearer to the house. If whole communities started planting this way, we’d create shared woodlands where the collection of plants and animals could live in relative balance.

Here’s how a suburban property and its neighborhood might bring back biodiversity by planting the boundaries with native shrubs and trees. Sketches by Jana Bryan, JMMDS.

Barilla states, “[W]e humans are responsible for the current changes. So we must also be responsible for helping other species survive them.”

Let’s get out and plant natives, just as Doug Tallamy suggests, and help bring back biodiversity to our landscapes, wherever we live.