By Anna Johansen, JMMDS

Following Julie’s jubilant call to action citing the teachings of Doug Tallamy to incorporate native plants in our landscapes, you may be wondering just how to take the next step. If so, read on!

Two gorgeous native plants with different environmental requirements. L: Chelone lyonii (pink turtlehead) loves wet feet. Photo: North Creek Nurseries. R: Lupinus perennis (sundial lupine) thrives in poor, dry soil. Photo: Wikimedia.

Imagine a front meadow rather than a front lawn, a woodland filled with native wildflowers rather than invasive honeysuckle and buckthorn—a home landscape that is resource-efficient, manageable, ecologically supportive, and beautiful. Last month I was fortunate to attend the New Directions in the American Landscape (NDAL)’s 3-day course, “Natural Landscape Design: Meadows & Woods,” whose subject matter was just that.

The course, headed by Larry Weaner (natural landscape designer and founder of NDAL) and supported by botanist and designer Ian Canton, forest ecologist, author and founder of Antioch’s Conservation Biology master’s degree program Tom Wessels, and Henry Art, Professor of Biology and Ecology at Williams College, left me brimming with its practical implications and a whole new perspective on human relationships with landscapes: What if instead of trying to control every detail of our landscapes we become facilitators, helping nature to establish sustainable plant communities in our yards? While the material was tailored to landscape design and management professionals, the overarching concepts are invaluable to every homeowner with a few blades of grass.

Mowing, mulching and weeding… if these words bring joy into your heart, then it’s probably best to stop reading here. But if, like me, you think of lost time and futility, then you might also be ready to shift your perspective. We can think like ecologists as we work in our gardens by observing natural processes and site conditions, nurturing plant relationships, being facilitators of change, and letting go.

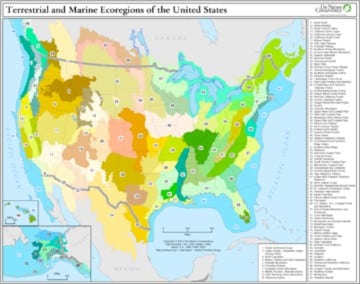

Determining your ecoregion is the first step to identifying plants native to your area. Map of Terrestrial and Marine Ecoregions of the United States: The Nature Conservancy.

Observation. Identify the existing plants in your landscape. Are they native or invasive? Are there native (or specialist) species that are thriving? Knowing that your hillside has a strong population of lowbush blueberries (which love acid soil) or that your woods have stands of maidenhair fern (which thrives in alkaline soil) takes the guesswork out of your soil type and pH, for example. If your land is overrun with invasives, or if you’re looking to plant a bare newly-constructed site with natives, you might get a soil test or find out from your neighbors which native plants are doing well in their yards. You can also determine your ecoregion and do some research to identify your target plant community.

L: Vaccinium angustifolium (lowbush blueberry), an acid loving plant. Photo: MSUE. R: Adiatum pedatum (maidenhair fern), a calciphile. Photo: Bosky Dell Natives.

Site Conditions. If there are bone-dry areas of your yard and saturated sections, use the opportunity to establish plants that will benefit from those conditions. Matching the plant’s needs to your site, rather than trying to amend your site to suit a plant, will conserve resources and possibly lead you to discover plant varieties much more interesting than your nursery’s usual offerings. Use your state’s Natural Heritage Program to determine which native plants thrive in your existing conditions.

Plant Relationships. Natural species have evolved together for many millennia. We may never be able to understand fully the complexity of these relationships, but observation and emulation lead to stability of the system. Think of a garden bed or your front lawn as a microcosm of succession. If you were to seed an area with r-selection species like columbine, which is known for being short-lived and reseeding vigorously, while also plugging it with young echinacea plants and other K-selection species, which will be around for the long haul, the columbine will grow quickly and fill in (no mulch!), while the echinacea more slowly establishes, eventually shading out the columbine and creating a strong weed-less stand.

L: Look closely, and you’ll see all the little seedlings at the base of this Aquilegia canadensis (columbine). Photo: GardenWeb. R: A strong stand of Echinacea pallida (pale purple coneflower). Photo: Missouriplants.com.

Natural (or native) garden establishment utilizes larger natural processes while capitalizing on specific traits of specific species. With this understanding, transforming your lawn into an annually mown and beautiful meadow or targeting the Achilles heel of invasive plants in your woods to restore wildlife habitat is completely attainable. I am not suggesting that we all become ecologists and horticulturalists, but those of use who shift our perspective from controller to facilitator are taking the first step.

To read more, check out articles by Larry Weaner.

For seeds and resources, look to Ernst Conservation Seeds.

I was startled when a landscape designer visiting my Portland, Oregon, garden dismissively called my stand of Mahonia aquifolium. “That’s just stuff in the woods.”

I’ve planted a stand of them in a highly problematic area, under the drip-line of sequoia. Not much soil, tons of needle constantly dropping… From small gallon plants to a thriving year round glossy evergreen screen, those plants are doing just what I’d hoped for, with almost no care! Early blooming for the local insects…berries for the birds…

The sequoia is the only big tree on the property, it’s amonster. Her comment did make me re-see the area. Though its a one tree forest, the mahonia makes it a woods.

For me, the tipping point toward seeking out native plants came when I noticed an ancient, twisting American hornbeam in a local garden park, then found it on a smaller scale everywhere in the woodland edge of a home site in the North Carolina mountains. I have two of them now rising in what’s becoming a woodland border. Another, planted as a specimen in the front lawn and vandalized down to a 10-inch stub, bounced back immediately after its trauma and is now thriving in full sun, putting out its first big crop of blooms last year.

For many years, the New England Wild Flower Society has been promoting the use of native plants in the home landscape, and educating the public about their value. The headquarters of the Society at Garden in the Woods in Framingham, Massachusetts, is a showplace especially in the spring when the wildflowers, including hundreds of lady slippers, are in bloom. Paths lead the visitor through various mini ecosystems illustrating the wide range of choice available to the home gardener. Native plants are for sale there, and also at the society’s nursery Nasami Farm in Whateley, Massachusetts. Thank you, Julie, for your strong support of the use of native plants in landscape design.

It’s great to read these comments! Thank you for sharing.

Patrick and Sue, how fortunate that you appreciate the value of your “stuff in the woods.” Your experiences are further proof that native plants reward us for including them by thriving and requiring little maintenance.

Anne, I have been to Nasami Farm and was so impressed; I’ll be back this spring for some natives for my garden. Also hoping to get to Framingham for the spring display this year!

Wonderful comments, everyone! Keep them coming!

I want to also mention the excellent “Native Plants in the Landscape Conference” at Millersville, PA that runs from June 1 through June 4th, with wonderful speakers, and plants and books for sale. I spoke there some years ago and was most impressed. Here’s their website: http://www.millersvilleneativeplants.org.

Their stated mission is “to increase the knowledge, propagation, cultivation, and use of native plants in the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions; to promote methods of land management and design that respect ‘sense of place’ by preserving and restoring native species and natural processes; to engender an appreciation of regionally appropriate landscapes that are harmonious for people and nature.”

If any one reading this blog is from Long Island New York i would like to share with you that The long Island Perennial Farm Located at 159 Reeves Avenue , Riverhead, New York , has it’s opening day April 22nd. Their phone # is 631- 727- 0009. For Long Islanders this is the place to go for Native plants to this area.

Hi,

I’ve noticed there is a dead link for the word ‘calciphile’ in the caption of blueberry and ferns image.

The glossary has been removed but the term is described here fully: https://www.gardenlifepro.com/glossary-botanical-terms/#calciphile

Kind Regards,

Jason

We updated the link, Jason! Thanks for calling this to our attention.