Soon after my honeymoon with Steve in 2002, I wrote this piece as a tribute to the beauty of this Caribbean island. Years later, the experiences are as vivid as the photos:

View from a villa at the Stonefield Estate Resort. Photo: Stonefield Estate.

…but what they had envied most in them

was the calypso part, the Caribbean lilt

still in the shells of their ears, like the surf’s rhythm,

until too much happiness was shadowed with guilt

like any Eden…

Omeros by Derek Walcott, p. 229

Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1992)

Imagine a shelter perched out and over a tropical rain forest facing a volcanic peak that rises nearly 3,000 feet above the sea. Picture its walls of white stucco, punctuated by wide shuttered doors and windows on all four sides, with ornately carved roof columns that hold up a flamingo-pink tin roof. An attached wooden deck hangs twenty feet above the jungle-like forest floor, complete with rope hammock that, along with the columns, perfectly frames the pinnacle in the near distance. When you throw open the brown-stained slatted doors, you find yourself in a cool tiled room with a lazily turning overhead fan hanging low from the eaves.

Gros Piton and Petit Piton. Photo: USA Today.

Within, two rum punches adorned with bougainvillea blossoms await. Behind more slatted screens lies a high four-poster bed veiled in mosquito netting. Opening the carved wooden door of the adjacent bathroom, you discover an outdoor walled garden of tropical plants and a banana tree with a bunch of green bananas that ripen slowly over the space of a week. Tiles frame a tiny terrace, the place you stand to take your showers as the geckos and snails watch.

This is the spot you’ve chosen for your midlife honeymoon, as Steve and I did—and it could not be more perfect. During the day, trade winds blow across the mountains and shake the papery leaves of the palm trees, draping the clouds across the face of the sacred peak before they exit out across the azure-blue sea. Sudden brief downpours open up the sky, monsoon-like, and douse everything and everyone in sight. Lizards and other nocturnal critters emerge in the lamplight, and you spend hours on end watching the lithe, lime-hued creatures poised patiently to pounce on errant moths and mosquitoes. At night, you play cards, read a bit, but mostly fall in bed to a ferociously deep sleep, peppered with the sounds of peepers and birds combining with the unintelligibly deep sounds of the surrounding bush.

L: St. Lucia is just south of Martinique; R: A closer shot of the island. Maps: Islandbrides.com.

This is St. Lucia, one of the windward islands that form an arc to make up the West Indies. The island is a mere twenty-seven miles long by fourteen miles wide; a jewel-like setting of mountains falling down to the sea, sliver-like harbors, and an impassible interior of rainforest that occupies over 19,000 acres in the interior of the island. The part of the countryside that is arable is often cultivated with bananas, a major contributor to the island’s economy. Other exports include cocoa, coconuts, mangoes, breadfruit, citrus, and spices.

Castries was corrupting him with its roaring life,

its littered market, with too many transport vans

competing… (p. 231)

The north of the island is inhabited by 40,000 of St. Lucia’s 150,000 people, most living in the thriving capital city of Castries. Here and in neighboring Rodney Bay, large hotel complexes and villas house holidaymakers and honeymooners and massive cruise liners dock their vessels and periodically flood the already teeming streets with eager shoppers who buy sarongs, bags, caps, wooden sculptures, carved coconut shells, spices, hot sauces, and other traditional Caribbean delights in the covered markets. And even Kentucky Fried Chicken has found its home in various spots around the island, although the neighborhood restaurant remains the local favorite.

L: An Arawak petroglyph; R: In the town of Soufrière. Photos: L: Dalitz.co.uk; R: Wikipedia.

Arriving at midnight at the little airport in Castries in the driving rain, we were just glad to finally have landed. We had had a wretched trip, being ill with the residue of a flu bug, and missing our connection in Puerto Rico, we endured a nine-hour layover, thanks to long security lines in Boston. Our taxi driver, Marcus, drove us to the southern part of the island over hairpin turns alongside vertical drops and through sleeping fishing villages. At long last, at 2 AM, we arrived at our destination. As we dragged our aching bodies out of the car and walked onto the deck of “Jasmine,” our villa for the next week, we noticed a vast conical form rising out of the vegetation in the middle distance, veiled by fog. Unsure as to what exactly it was, it wasn’t until we woke up ten hours later that we realized exactly where we were.

He yawned and watched the lilac horns of his island

lift the horizon. (p. 156)

Our villa is at the most picturesque spot on the island—to the south at the base of the Petit Piton, the sacred volcanic cone that we look out upon. Lying for hours in my hammock studying its crags and crevices, and mantle of stunted trees, I take to bowing my head in reverence whenever I greet it. It rises over 2700 feet from the sea and was thought by the early Arawak peoples to be house a female deity: a sacred mother and child mountain. According to locals, the rocky spur that juts from her lower left side represents her child. Her male counterpart, the Gros Piton, lies a mile or so away and to our eyes, while a few hundred feet higher and broader, seems less picturesque. The Arawaks left behind vestiges of their rites of worship in the petroglyphs on our property, here at the Stonefield Villa Estate.

L: Soufrière and Les Pitons beyond; R: Colorful boats line the shore. Photos: L: Keyposters.com; R: Planetware.com.

Stonefield’s own history mirrors the history of agriculture in St. Lucia. Built in the 18th century as a sugar cane plantation, a spate of hurricanes and the abolition of slavery caused its owners to replant it in limes, useful for preserving food before refrigeration was introduced. Just before World War II, it was planted in cocoa for export to Great Britain to make into chocolate. When the current owners, Wayne and Anista Brown, bought the estate from Lady Erskine, a daughter of Admiral Kelly of the Royal Navy, in 1972, they converted it to a resort. Eleven villas occupy the 26 lush acres on which a “Nature Trail” has been created where the pre-Columbian rock carvings may be seen that date from 350 AD.

In my 1995 book The Inward Garden, I explore a theory of special vantages on the world, divided into seven fundamental forms of space. I believe that we subconsciously look at the world from these “archetypal vantages.” In my parlance, the Stonefield Estate is built as a series of promontory experiences—edge conditions that offer the viewer a chance to get up and out over the world, while being still connected to the land behind them. I believe that all the greatest vacation spots of the world enjoy similar features—and Stonefield Estate has the best vantage and focal points I’ve ever seen and has taken full advantage of it.

Some evenings, Steve and I would walk down the steep road into nearby Soufriere to get provisions, stopping to see out over the historic town from one of the many lookout points (which our driver called “The Kodak Moment”) along the winding roads of St. Lucia. Houses like a long, inhabited wall with common sidewalls line each street, with front doors opening right up onto the narrow concrete walkway and deep drainage channel that edge each side of the narrow road that runs through the center of Soufriere. At night, the houses are shuttered, the whole place battened down and closed up tight. A vegetable market and food stores ring the central square that fronts the large Catholic church. It was here that a guillotine was wheeled off a boat and wealthy French landowners executed during the French Revolution.

One day, we decided to walk up the steep, narrow road that encircles the island and visit the “drive-in volcano,” a few short miles from Stonefield. Our guide was named Thomas, a handsome man in his thirties with terrible teeth and a remarkable knowledge of island history. As we walked along the path that circled the bubbling and roiling sulphuric pools, he indulged all of our questions. St. Lucia, known as Helen of the West, was fought over so many times by so many countries and peoples. The first inhabitants were the Arawak Indians, who were eventually conquered by the warlike Caribs of South America around 1300. These same peoples fought the French and British in the early 1600’s, preventing them from inhabiting the island until the mid 1600’s, when French settlers finally established a colony on St. Lucia. Seven times, the British wrested control from the French, and another seven, the French took control from the British. Finally, in 1814, the British took control of the island, and finally gave St Lucia her independence in 1979.

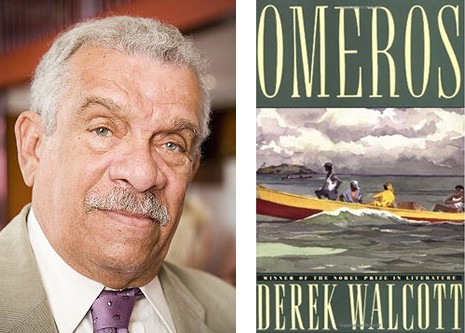

Poet Derek Walcott and the cover of Omeros. Photos: L: Wikipedia; R: Amazon.com.

St. Lucian native and Nobel prize-winning poet Derek Walcott captured the Helen of Troy metaphor in his novel-length poem, Omeros. Born in 1930 in Castries to a British father and West Indian mother, Walcott lives today in the US and in Trinidad. In his 1990 epic, Omeros, he fuses his own island background with classical ideals, and writes in three-line stanzas reminiscent of Dante’s terza rima. Based loosely on the Iliad and the Odyssey, the book mixes English with sprinklings of local patois dialect, French and Latin. In it, he likens St. Lucia to the beautiful Helen of Troy—the face that launched a thousand ships and over whom men and countries fight.

Mamiku Gardens. Photo: Strabon-Caraibes.org.

Towards the middle of our week, we decided to explore the island so we rented a four-wheel drive vehicle. The first day, we discovered Mamiku Gardens on the east coast, named for its original owner, Madame Micoud, an 18th century historical site with a dramatic story of an enterprising French woman who raised her family and managed the sugar cane estate, while her husband was off fighting wars. Brigands—freed slaves who turned against their former masters, fought troops brought in from Guadeloupe on the Mamiku estate as Mme. Micoud escaped with her children and her life. She returned, rebuilt the estate, and turned it into a banana plantation. The Shingleton-Smith family bought it over fifty years ago, and Veronica, now in her seventies, turned fifteen of its acres into gardens a mere four years ago. My favorite parts are the interpretive walking trails to the old house site on the top of the hill, with views cut out to the rocky shore and ocean below; the stream garden walk, the orchid collections, and the allees of bougainvillea bushes, all abloom in shades of fuchsia, peach, and soft pinks. It is a remarkable achievement in a short time, and, along with the more formal Botanical Gardens in Soufriere, deserves to be seen by all who visit St. Lucia.

He fitted the trawling rods. Achille felt the rim

of the brimming morning being brought like a gift

by the handles of the headland. He was at home.

This was his garden… (p. 126)

But for this landscape designer, the more fascinating “garden” was the natural one found in the Edmund Forest, the most beautiful rain forest I have ever seen, reached by one of the worst roads I’ve ever driven. Passable only by a 4-wheel-drive vehicle going about 6 miles an hour, its numerous ruts, potholes, and washouts had us laughing and holding on for dear life. At 1800 feet above sea level, we reached our destination, and found a group about to descend with a guide. He offered walking sticks and led us single file down steep and winding trails deep into cloud forests and elfin woodlands. Our guide pointed out the growth habits of the tree fern; how its bark is used as treadstock for steps along the twenty-nine miles of paths cut into the rainforest by the Forestry Service. He showed us how bromeliads lived on trees, pointed out rare birds and parrots, and had us smell ginger root growing along the path. When we finally reached the bottom, we swam in a pool below a waterfall, thus the name of the place: En Bas Saut, “below the falls.” To our relief, the way up was a different route than the way down; less steep, it also ended up down the original road, with the last half-a-mile rising through forest department lands cultivated with all sorts of tropical flowers; anthuriums, birds-of-paradise, bougainvilleas, heliconia to name just a few. It felt like we were ascending into heaven.

Soufrière at night. Photo: Wikipedia.

St. Lucia is a hard place to leave. Sunburned, rested, and yes, a tiny bit spoiled, I said my goodbyes to the Petit Piton, and, with my new husband, left Stonefield in the early morning mist, traveling back over the same hairpin turns, past the same overlooks, back into the civilization that is Castries. Some hours later, we boarded the small jet that took us to the larger 767 that brought us back to Boston and the lives we had already known. I have been blessed to see many beautiful places in this world; I believe that our perch looking out on the Petit Piton was the most sublime.

A post I’ll return to again and again! Beautiful!

Thanks for the tip on finding paradise!

Sounds beautiful. Maybe one day my wife and i will get there. Without the Kids of course.

Thank you so much for this article. You put into words feelings & experiences that I could never have explained. I have listened to my parents stories for years and visited the island twice myself while growing up. I have taken our family’s history and passion about the island and created a line of jewelry to honor the beauty of the place and it’s people. Cannot wait to return one day.

Cressida,

Please post a link for us so we can see your jewelry. It sounds magical!