Text and photos (except where noted) by Jennifer Silver, JMMDS

Gas prices have been going up, and with them, food prices. This winter I was shocked by my family’s grocery bills and determined that we would start growing a lot more of our own food. Trying to be as self-reliant as possible, we grow a wide variety of fruits and vegetables. Every year some crops do well, others languish, some fail spectacularly. We were philosophical about the losses, but now I mean to combat them more vigorously.

Some of the most welcome signs of spring: happy, snappy peas and garlic!

For a few years, while working in other people’s gardens, I was scrupulous about testing their soil, correcting imbalances, using crop-specific fertilizers, weeding, and mulching. At home in my own garden, I adopted a laid-back, low-maintenance, “if it doesn’t thrive here, fahgeddaboutit” approach. No more of that! It’s time to make the most of every square foot of garden space.

The first major change that I am making is how I prepare my garden beds. As I’ve written before, I dig rather than till, disturbing the soil structure as little as possible. For crops that hate acid soil (i.e., most of them), I add a dusting of lime. This year, for the first time, I am incorporating a homemade COF (complete organic fertilizer) into the soil of every bed before planting.

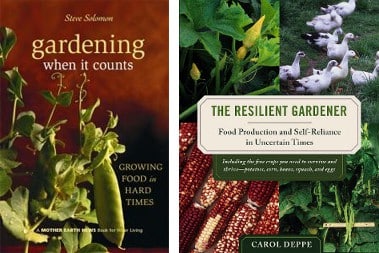

L: Gardening When It Counts: Growing Food in Hard Times by Steve Solomon. Photo: New Society Publishers. R: The Resilient Gardener: Food Production and Self-Reliance in Uncertain Times by Carol Deppe. Photo: Amazon.

I previously thought homemade compost was a perfectly good addition to the soil—and the only one necessary. After reading the excellent books Gardening When It Counts by Steve Solomon (founder of Territorial Seed Company) and Carol Deppe’s The Resilient Gardener, I understand that while compost adds wonderful organic matter to the soil, vastly improving its tilth, it doesn’t do nearly enough to feed annual vegetable crops. Quite honestly I tried to resist this truth for a while (in part because of a tetchy vanity about the quality of my compost); however, thinking back to some of last year’s lackluster harvests, I am persuaded to try it.

Hey, veggies, whatsamatta?! This beautiful stuff ain’t good enough for ya?

I used Solomon’s COF recipe, which calls for the following:

- 4 parts seedmeal (any kind except coprameal) or 3 parts seedmeal and 1 part tankage (meatmeal)

- ¼ part agricultural lime, finely gound

- ¼ part gypsum

- ½ part dolomitic lime

- 1 part of any of the following: rock phosphate, bonemeal, guano, kelpmeal, basalt dust (½ part)

He also suggests some alternatives and substitutions, which I won’t list here. He warns that parts must be measured by volume, not weight. I used an old 2-quart saucepan to measure out equal parts.

So, here are the ingredients I used, with actual quantities:

- 6 quarts cottonseed meal

- 2 quarts dried blood (instead of meatmeal)

- ½ quart agricultural lime, pulverized

- 1 quart dolomitic lime

- ½ quart gypsum

- 1 quart rock phosphate

- 1 quart bonemeal

- 1 quart kelpmeal

I chose ingredients based on what was available, which were least expensive, and what I already had on hand (the bonemeal and kelpmeal). It occurs to me that you might like to know how much I spent on these ingredients, so I’ll try to dig up my receipts later and post them as a comment. As Solomon points out, the money is well spent in terms of dollars saved at the grocery store and the much higher nutritional content of veggies grown with COF. It can also save time; correctly used, COF distributes the perfect amount of lime, so you won’t have to lime the garden as a separate step.

Ah, the magic formula: complete organic fertilizer (recipe above).

I store my COF in covered plastic 5-gallon buckets (it filled 2½ buckets) with a handy measuring scoop nearby. How much to add to garden beds? Solomon says to add 4-6 quarts per 100 square feet (or 10 square meters). If planting in long rows, use 4-6 quarts per 50 feet of row (in a 12-18″-wide band). If you have clay soil, as I do, use 1½ times this amount for the first few years. Dig it in well to a depth of about 12 inches. Solomon and Deppe also give specific advice for preparing beds for individual crops, so I highly recommend reading (and highlighting) both books.

When we had that crazy heat wave back in March, which dried out the soil much earlier than usual, I planted a few beds with cover crops such as oats and buckwheat (seeds I already had on hand). The heat-loving buckwheat is just sort of pathetically limping along, but the oats are coming along nicely, providing some good biomass to add organic matter to the soil. Next week I’ll turn it all in and let it decompose. By June 1, when it’s time to put in peppers, eggplants, tomatoes, and squash, the cover crops should be well broken down.

“Mares eat oats, and squash eat oats…”

“Mares eat oats, and squash eat oats…”

Cover crops can help feed your soil (and therefore whatever else you plant there).

As always, I’ll continue my lazy-gardener’s favorite technique of using leaf mulch to prevent weeds and add tilth to the soil as it breaks down. I will also be more vigilant this year about reading up on which crops like what kind of fertilizer when, instead of my habitual sloppy “This-week-everybody-gets-fish-fertilizer!” feedings.

I’ll try to keep you posted on the results. In the meantime, please share your comments, experience, resolutions, triumphs, and lessons learned!

I would consider taking a soil test before using a recipe. For instance, in the piedmont area of VT, the soil pH is often very good and the lime and dolomite would be a waste of money–this was the case with my garden in Saxtons River. Also, in some cases there is plenty of magnesium so you would not want to use dolomite even if you need to adjust pH. In the more mountainous area, the pH is often quite acidic and more lime might be needed than in this recipe. Compost can actually be a very good source of P and K making the rock phosphate, bonemeal, and basalt less valuable. I wouldn’t sell your compost short –unless the soil test shows you otherwise.

The phosphorus in rock phosphate is largely unavailable, and is a depleting resource from human over use.

In lack luster years, the problem is most likely nitrogen which the kelp, seed meal and quano can help with. But, growing clover and other legumes, whenever and wherever you can would be a cheaper and more environmentally sound source.

Short of a soil test, I like your old approach of compost and cover crops better than what these book authors are preaching.

It’s been the hardest lesson for me to learn (as a plant ecologist by background) that vegetables are nutrient and water hogs!

They need lots more nutrients than I’ve ever imagined, and it’s way beyond compost.

The vegetable gardens (at the botanical garden where I work) that are enriched with either chicken manure or goat manure grow amazingly productive vegetables. Mine at home (enriched with compost and a bit of composted manure and mushroom compost do fine) — but!

Great post.

Thanks, Lisa!

You have a beautiful blog yourself. I read that you were experiencing a dry spell (as we did here in VT) through April. Did sufficient rains finally come? I was very worried about a dry season, but we’ve been getting a good soaking the last two weeks.

Would love to share some of your blog posts with our readers, if you’re agreeable!

Hi, Mike! Thanks for this comment–excellent advice. I was not aware of the issues around rock phosphate. I have tested the pH of the soil in my Rockingham garden, and it is very acidic, but I haven’t sent in samples for a full workup from UVM Extension. What am I waiting for?!

Hope to see you at the BF Farmers’ Market!

Did you find your receipts? I’d love to know costs on the COF.

Oops! I forgot. Thanks for the nudge…I’m writing myself a note to do it this weekend. Please check back on Monday!

Okay, here’s the breakdown:

6 quarts cottonseed meal – about $3

2 quarts dried blood (instead of meatmeal) – about $3

½ quart agricultural lime, pulverized – less than $1

1 quart dolomitic lime – less than $1

½ quart gypsum – $7

1 quart rock phosphate – $10 (but I will never buy again! See May 15 blog!)

1 quart bonemeal – $7

1 quart kelpmeal – $15

Total: about $46. I’ve used about 2/3 of it, so there’s some left for next year. Hope that’s helpful!